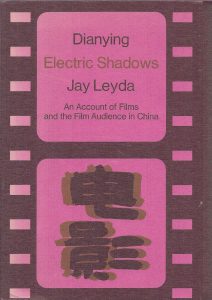

Dianying/Electric Shadows: An Account of Films and Film Audience in China

by Jay Leyda

MIT Press

515 pages, 1972

ISBN: 9780262120463

Publisher website: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/dianyingelectric-shadows

Publisher’s description:

Films have for some time been an important element in Chinese art and society, and filmmaking is a strenuous business—characterized by “the old problem of official Chinese sensitivity about Chinese reality,” by deep conflicts, and by the necessity of designing films for and transporting them to millions of peasants throughout the Republic.

Because he worked with the Chinese film industry in Peking from 1959 to 1964, the author has had access to more Chinese films and relevant documents than any other Western scholar. In Dianying he describes both historic and current film production, using the films themselves as primary source material. He covers the film industry (the rise and fall of film studios, the influence of foreign filmmakers, the problems of film distributors), gives synopses of important and representative films, and introduces us to the notable filmmakers, actors, and actresses of China.

Dianying also throws light on the larger social and political scene in twentieth-century China. It reveals a dramatic and astonishing period of Chinese film history during which an underground group of revolutionaries made films that continued to reach large audiences despite Kuomintang and Japanese oppression. What is significant, Leyda points out, is that the most expressive and lasting Chinese films resulted from these bitter and often bloody circumstances—films that were superior to what came before and in many respects superior to films made well after the triumph of the Chinese revolution.

Jay Leyda has found things of value in films from almost all periods of development: “Seeing a steady quantity of Chinese films,” he remarks, “I found myself imagining, too easily, that if there had been films in the Middle Ages, this is what they would have looked like. Here are the conformity, the self-satisfied and defensive insularity, the almost scientific reduction of personal interpretation to its minimum, the rigid stratification of social groups…, the fixed place for each individual, and the molding of people to types that we find in medieval arts, with rare exceptions. There are the same rare exceptions in Chinese cinema, I’m glad to see, for it’s only from such brave exceptions, recognizing the values of humanity and art, that we can expect any progress to grow—or a socialist cinema to tear itself away from feudalism. These exceptions make me hopeful for China’s future and film future; without this hope there would be little point in this book.”